| 第40行: | 第40行: | ||

This is a fundamental limitation of the way the HTTP/1.1 protocol was designed. If you have a single HTTP/1.1 connection, resource responses always have to be delivered in-full before you can switch to sending a new resource. This can lead to severe HOL blocking issues if earlier resources are slow to create (for example a dynamically generated index.html that is filled from database queries) or, as above, if earlier resources are large. | This is a fundamental limitation of the way the HTTP/1.1 protocol was designed. If you have a single HTTP/1.1 connection, resource responses always have to be delivered in-full before you can switch to sending a new resource. This can lead to severe HOL blocking issues if earlier resources are slow to create (for example a dynamically generated index.html that is filled from database queries) or, as above, if earlier resources are large. | ||

= HOL blocking in HTTP/2 = | |||

As such, the goal for HTTP/2 was quite clear: make it so that we can move back to a single TCP connection by solving the HOL blocking problem. Stated differently: we want to enable proper multiplexing of resource chunks. This wasn’t possible in HTTP/1.1 because there was no way to discern to which resource a chunk belongs, or where it ends and another begins. HTTP/2 solves this quite elegantly by prepending small control messages, called frames, before the resource chunks. | |||

[[Image:4_H2_1file.png|600px|border]] | |||

2023年12月8日 (五) 03:24的版本

Head-of-line blocking (HOL blocking) in computer networking is a performance-limiting phenomenon that occurs when a line of packets is held up in a queue by a first packet. Solving HOL blocking was also one of the main motivations behind not just HTTP/3 and QUIC but also HTTP/2.

The HOL blocking problem

It’s difficult to give you a single technical definition of HOL blocking, as this blogpost alone describes four different variations of it. A simple definition however would be:

When a single (slow) object prevents other/following objects from making progress

A good real-life metaphor is a grocery store with just a single check-out counter. One customer buying a lot of items can end up delaying everyone behind them, as customers are served in a First In, First Out manner. Another example is a highway with just a single lane. One car crash on this road can end up jamming the entire passage for a long time. As such, even a single issue at the “head” can “block” the entire “line”[1].

This concept has been one of the hardest Web performance problems to solve.

HOL blocking in HTTP/1.1

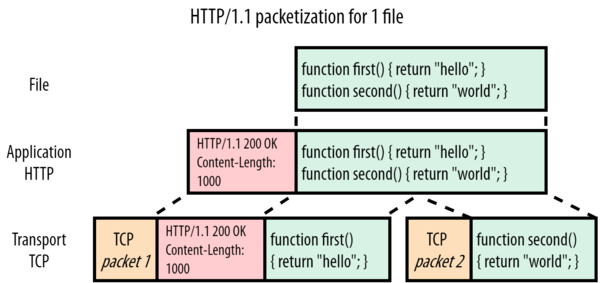

HTTP/1.1 is a protocol from a simpler time. A time when protocols could still be text-based and readable on the wire. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below:

We can see that the HTTP aspect itself is straightforward: it just adds some textual “headers” (red) directly in front of the plaintext file content or “payload”. Headers + payload are then passed down to the underlying TCP (orange) for actual transport to the client. For this example, let’s pretend we cannot fit the entire file into 1 TCP packet and it has to be split up into two parts.

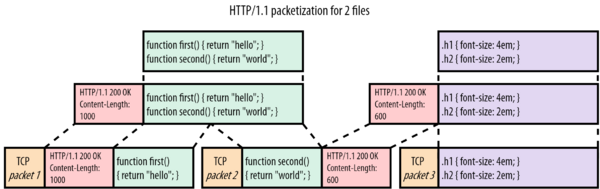

Now let’s see what happens when the browser also requests style.css in Figure 2:

In this case, we are sending style.css (purple) after the response for script.js has been transmitted. The headers and content for style.css are simply appended after the JavaScript (JS) file. The receiver uses the Content-Length header to know where each response ends and another starts (in our simplified example, script.js is 1000 bytes large, while style.css is just 600 bytes).

All of that seems sensible enough in this simple example with two small files. However, imagine a scenario in which the JS file is much larger than CSS (say 1MB instead of 1KB). In this case, the CSS would have to wait before the entire JS file was downloaded, even though it is much smaller and thus could be parsed/used earlier. Visualizing this more directly, using the number 1 for large_script.js and 2 for style.css, we would get something like this:

11111111111111111111111111111111111111122

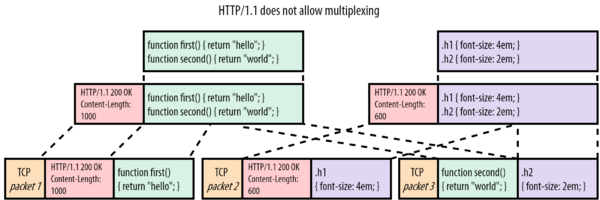

HTTP/1.1 does not allow multiplexing

The “real” solution to this problem would be to employ multiplexing. If we can cut up each file’s payload into smaller pieces or “chunks”, we can mix or “interleave” those chunks on the wire: send a chunk for the JS, one for the CSS, then another for the JS again, etc. until the files are downloaded. With this approach, the smaller CSS file will be downloaded (and usable) much earlier, while only delaying the larger JS file by a bit. Visualized with numbers we would get:

12121111111111111111111111111111111111111

The main problem here is that HTTP/1.1 is a purely textual protocol that only appends headers to the front of the payload. It does nothing further to differentiate individual (chunks of) resources from one another.

This is a fundamental limitation of the way the HTTP/1.1 protocol was designed. If you have a single HTTP/1.1 connection, resource responses always have to be delivered in-full before you can switch to sending a new resource. This can lead to severe HOL blocking issues if earlier resources are slow to create (for example a dynamically generated index.html that is filled from database queries) or, as above, if earlier resources are large.

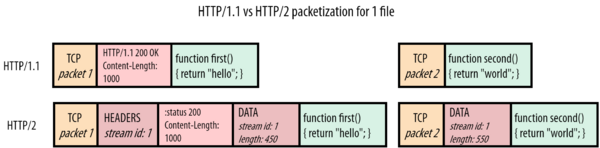

HOL blocking in HTTP/2

As such, the goal for HTTP/2 was quite clear: make it so that we can move back to a single TCP connection by solving the HOL blocking problem. Stated differently: we want to enable proper multiplexing of resource chunks. This wasn’t possible in HTTP/1.1 because there was no way to discern to which resource a chunk belongs, or where it ends and another begins. HTTP/2 solves this quite elegantly by prepending small control messages, called frames, before the resource chunks.